“All intelligent investing is value investing, acquiring more than you are paying for.”

Get your Free

financial review

The danger signs had been visible for quite some time, for those with the eyes to see. As early as October 1967, Warren Buffett was writing to his partners at the Buffett Partnership Ltd., warning that:

“The market environment has changed progressively.. resulting in a sharp diminution in the number of obvious quantitatively based investment bargains available..

“In my opinion what is resulting is speculation on an increasing scale.. we will not follow the frequently prevalent approach of investing in securities where an attempt to anticipate market action overrides business valuations. Such so-called ‘fashion’ investing has frequently produced very substantial and quick profits in recent years.. It does not completely satisfy my intellect (or perhaps my prejudices), and most definitely does not fit my temperament. I will not invest my own money based upon such an approach – hence, I will most certainly not do so with your money.”

By November 1967, Buffett was going to some lengths to manage his partners’ expectations. He pointed out that the partnership had $20 million invested in “controlled companies” (i.e. unlisted subsidiaries) and a further $16 million in short-term government debt – a total of $36 million in partners’ capital that would not benefit in any way from a stock market rally. This was not a judgment call on the level of the market, however, merely a reflection of the fact that “I can’t find any obviously profitable and safe places to put the money”.

By May 1969, Buffett had had enough. He wrote to advise his partners that he was winding up the partnership for good:

“I just don’t see anything available that gives any reasonable hope of delivering.. a good year and I have no desire to grope around, hoping to “get lucky” with other people’s money. I am not attuned to this market environment, and I don’t want to spoil a decent record by trying to play a game I don’t understand just so I can go out a hero.”

While Buffett was in the process of quietly exiting the stock market, other investors were piling into the shares of businesses that would become notorious as the ‘Nifty Fifty’ – those ‘glamour’ stocks, like IBM, Gillette, Coca-Cola and Xerox, that seemed to offer such stability (virtually none of them had cut their dividends since World War 2) combined with such superior prospects for growth (including international expansion) that they could justify practically any valuation afforded them by the marketplace, and defy any apparent weakness in the global economy.

The ‘Nifty Fifty’ came to be known as ‘one decision’ stocks: the only decision investors had to make was just how many of them to buy.

By 1972, the S&P 500 index was trading at a punchy 19 times earnings. The ‘Nifty Fifty’, on the other hand, stood at a p/e of 42. That was the average. Some of the individual nifties traded at eye-watering levels, factoring in a ridiculous level of optimism for the future. Avon Products traded at 65 times earnings. Walt Disney stood at 82 times. McDonald’s was at 86 times earnings. Polaroid sported a p/e of 91.

And then the market collapsed.

In the words of a Forbes columnist, the Nifty Fifty “were taken out and shot, one by one.”

From its high, Xerox stock fell by 71%. Avon Products fell by 86%. Polaroid’s decline was the most sickening: 91%.

Forbes issued a post mortem for these former wonder stocks:

“What held the Nifty Fifty up ? The same thing that held up tulip-bulb prices in long-ago Holland – popular delusions and the madness of crowds. The delusion was that these companies were so good it didn’t matter what you paid for them; their inexorable growth would bail you out.

“Obviously the problem was not with the companies but with the temporary insanity of institutional money managers – proving again that stupidity well-packaged can sound like wisdom. It was so easy to forget that no sizable company could possibly be worth over 50 times normal earnings.”

The bizarre thing about the investment markets is that if you simply hang around long enough, you get to see insanity repeat itself. Human nature never really changes. It took roughly a generation for the cult of the Nifty Fifty to repeat itself with the first wave of dot-bombs in 1999. Since we now operate in internet time, the delays between these peak waves of insanity are getting shorter and shorter. The Nifty Fifty has put in some recent reappearances, in the form of numerous cryptocurrencies, and a second (or is it third ?) Nasdaq mega-cap boom.

Like the Nifty Fifty, support for, and investor interest in, the wildly popular global tech mega-cap brand, for example, had a superficial grounding in reality. Financial repression had driven interest rates down to zero and in some cases below it. That essentially destroyed (and we think continues to invalidate) both cash and bonds as relevant asset classes for most investors – especially individuals – and effectively forced them into the welcoming embrace of the equity markets, in search of a positive real return. But which stocks to own ? Those investors who have stampeded into global mega-cap brands have done so for sane enough reasons. They think these stocks are safe. The businesses may well be, but safety in matters of investment is a function of price and valuation, not business quality. It is, in other words, all about value.

Many investors claim to be value investors, but what do they really mean by the term ?

Value is somewhat subjective, and to some extent it’s in the eye of the beholder. Your definition of value and ours are likely to be somewhat different. Human nature is like that. We have different preferences, different risk tolerances, different objectives.

But we all want a good deal.

Along the continuum of investing strategies, ‘deep value’ sits at one end: it is what Warren Buffett once described as ‘cigar butt’ investing – a cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it. It may not offer much of a smoke, “but the bargain purchase will make that puff all profit”.

Benjamin Graham, the spiritual father of value investing, recommended a particular type of ‘deep value’ opportunity in the form of so-called ‘net net’ stocks. A ‘net net’ stock is one where a company’s net cash and liquid assets add up to more than the entire market capitalisation of the company. In effect, you’re getting the business for free.

Two separate studies of ‘net nets’ point to the returns available from value investing.

The first, conducted by Professor Henry Oppenheimer across the US stock market between 1970 and 1983 (‘Ben Graham’s net current asset values: a performance update’) showed some impressive results. Whereas the market itself returned 11.5% per annum over the period in question, net net stocks returned 29.4% per annum. Almost three times as much.

The second, conducted by the behavioural economist James Montier, across global markets between 1985 and 2007, saw the markets themselves deliver an annual return of 17%. Net net stocks, however, returned 35% – almost twice as much. Perhaps there could be something behind deep value investing ?

One of the best exponents of deep value investing we know is the US manager Dave Iben of Kopernik Global Investors. When we first heard Iben speak at a meeting in London we were struck by a consistent refrain of what he looks for in an investment:

“I want half off.”

Whatever he’s considering buying, he wants to buy at a discount. The minimum discount he’s willing to accept is 50%. And if whatever he’s buying is in a risky market where the quality of corporate governance may be somewhat questionable, or where political risk might be more than usually acute, he wants even more off – perhaps as much as 80% or 90% versus ‘fair value’. So although the quality of these investments may be a little questionable, the deep discount at which they are sometimes available amounts to a margin of safety, of sorts.

And the biggest risk associated with ‘deep value’ relates to quality. A ‘deep value’ business may well be cheap, but it may also be cheap for a reason. A ‘deep value’ business runs the risk of turning into a ‘value trap’ – its shares never end up recovering toward a share price consistent with an investor’s assessment of its fair value. Capital invested in a ‘value trap’ never manages to escape from a fundamentally poorly performing company. Value traps are the stock market’s equivalent of black holes.

‘Growth’ sits at the other end of the scale. A ‘growth’ stock is widely perceived to be a better investment because the company’s revenues (if not its profits) are growing strongly. It is typically in a sexy ‘growth’ sector, like biotechnology, alternative energy, or fintech. Growth investors are essentially momentum investors – for as long as the stock price is rising, growth investors are more than happy to chug along with it. The biggest risk associated with ‘growth’ stocks is that that growth suddenly goes into reverse. Company revenues stop growing as quickly as they have in the past, or – heaven forbid – they go into reverse. Internet stocks were the classic example of growth stocks during the mid- to late-90s. Companies without profits and in many cases without even revenues could justify pretty much any valuation, on the grounds that they were growing so quickly they could ‘grow into’ those elevated valuations over time. It was important for growth investors simply to stake their claim and exploit ‘first mover advantage’. That was the theory, anyway.

One of the more notorious examples of a growth stock advocate was Jim Cramer of financial website TheStreet.com in February 2000. Delivering the keynote speech at the 6th Annual Internet and Electronic Conference and Exposition in New York, Cramer named 10 technology and internet companies and then issued the following recommendation:

“We are buying some of every one of these this morning as I give this speech. We buy them every day, particularly if they are down, which, no surprise given what they do, is very rare. And we will keep doing so until this period is over – and it is very far from ending. Heck, people are just learning these stories on Wall Street, and the more they come to learn, the more they love and own! Most of these companies don’t even have earnings per share, so we won’t have to be constrained by that methodology for quarters to come.”

Famous last words.

It turns out that Cramer inadvertently nailed the top of the first Internet boom. His speech was delivered within a month of Nasdaq’s March 2000 high. Nasdaq went on to fall by 80% over the next two years. Growth investing comes at a price. Or as Warren Buffett put it, it is difficult to buy what is popular and do well.

Why Buffett isn’t a value investor

Between deep value on one hand and growth on the other lie a selection of value strategies. A few summers ago we attended the London Value Investor Conference at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, near Parliament. 500 value managers from around the world were packed into the auditorium. The first speaker asked the floor a question: what type of investor are you ? Are you a classic ‘value’ manager ? We put our hand up, but we didn’t have much company. He then asked, are you a ‘franchise’ manager ? Almost everybody stuck their hand up. Value is clearly in the eye of the beholder.

Warren Buffett began his investment career as a value manager in the style of Benjamin Graham. Benjamin Graham’s ‘The Intelligent Investor’, first published in 1949, remains the Bible of value investing. Graham went out of his way to define investment as opposed to speculation, as follows:

“An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

To Graham, an investment and a ‘value’ investment were essentially the same thing. Value simply offered a greater margin of safety to the investor.

But something happened to Warren Buffett along the way. His holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, became too big for him to concentrate on value investing.

Genuine value investing has its limits.

Genuine value investing, especially in small and mid-cap companies, has size constraints.

Warren Buffett faced these constraints. At the time of his recent retirement from it, Berkshire Hathaway was a $1 trillion company by market cap. During his more recent years at the company, Buffett could not realistically buy small or mid-cap stocks (if he desired any meaningful impact on his overall portfolio). Berkshire Hathaway was and is simply too big.

So as Berkshire grew, Buffett was forced to shift his emphasis from Benjamin Graham-style value to what we might call ‘franchise’ value instead: businesses that enjoy a superior reputation with relation to their brands beyond those businesses’ plain balance sheet value. Which is another way of saying ‘growth’ stocks, since their shares are typically trading at a significant premium to their fair value. Buffett is fond of buying businesses with a “moat”: some seemingly unassailable position in the marketplace deriving from a monopoly-type market advantage. But shares in those type of businesses don’t come cheap, because almost everyone wants to own them. As he’s admitted, because of the scale of Berkshire’s business interests, Buffett / Berkshire now has to look for the market equivalent of elephants in order to move the dial on his investment portfolio. And as the fund manager Jim Slater was fond of saying, elephants don’t gallop. Berkshire, in other words, has to compromise when it comes to paying, and potentially overpaying, to own quality businesses (in some instances, outright).

So when (almost) everyone at the London Value Conference confessed to being a ‘franchise’ manager, what they really meant was they had stopped being a ‘value’ manager – either because it’s too difficult, or because there are too few opportunities, or both.

The late Canadian value manager Peter Cundill nicely expressed this problem in his autobiography ‘There’s always something to do’. Specifically, he advised readers that

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

Your edge over the professionals

But this is an area in which, as an individual investor, you have an advantage over ourselves. You don’t have to disclose your investments to anyone. You don’t have to worry about inflows and especially outflows from your fund. You don’t have to report your performance on a daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly basis to anybody. As managers of a UK regulated fund we have to do all of the above. We’re comfortable with the swings and arrows of the market’s outrageous fortune – but our investors may not be, so we’re continually at the mercy of those inflows and outflows. As Peter Cundill correctly pointed out, most investors do not possess an overabundance of patience.

Which is a shame. Because value investing is the best performing investment strategy there is. In his fabulous study of market returns, ‘What works on Wall Street’ (we use the 2005 edition published by McGraw-Hill), James O’Shaughnessy points to the long term outperformance of value metrics versus growth.

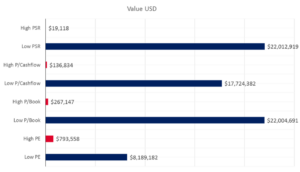

Take the following chart. It shows the compound annual average rates of return for various strategies drawn from the broader US market over a period of over 50 years.

Value of $10,000 invested in various strategies for the 52 years ending in December 2003

Source: ‘What Works on Wall Street’ by James P. O’Shaughnessy

The figures are illuminating, and the data set sufficiently large, in our opinion, to address any questions about selectivity or survivorship bias.

All of those metrics associated with ‘growth’ investing strategies (buying stocks on a high price to sales ratio (PSR), buying stocks on high price / cashflow, buying stocks on a high price / book ratio, buying stocks on a high p/e ratio) delivered significantly worse returns than those metrics associated with classic Ben Graham ‘value’ investing.

If you bought high yielding stocks – irrespective of the quality of the businesses – you made, on average 13.35%.

If you bought stocks on a high price / sales ratio, you did appallingly, averaging just 1.25% per annum.

But if you did the exact opposite, and selected stocks trading on a low price / sales ratio, you made out like a bandit, with average annual returns of 15.95%.

Price / cashflow saw the same effect. A ‘growth’ bias made you 5.16%, on average. A ‘value’ bias earned you 15.47%.

Price / book saw the same effect. A ‘growth’ bias gave you 6.52%, on average. A ‘value’ bias saw you earn 15.95%.

Price / earnings saw the same effect. ‘Growth’ investors favouring high p/e stocks earned 8.78%, on average. ‘Value’ investors favouring low p/e stocks earned 13.77%.

This analysis is staggering. The gulf between the long term returns from ‘growth’ and ‘value’ strategies is eye-opening. And note, again, that this study takes no account of the more subjective, qualitative aspects of investing such as the quality of the business or the calibre of management – this is just raw data we’re looking at.

But the message is clear. While ‘growth’ stocks can clearly outperform over the shorter term, ‘value’ wins out for the patient investor. Take the (first) Nasdaq boom of the late 1990s. ‘Growth’ stocks delivered stellar returns for a few years – and then gave them all back, with interest. ‘Value’ underperformed for a period, but any patient ‘value’ investor was vindicated from March 2000 onwards.

As O’Shaughnessy puts it,

“..anyone familiar with past market bubbles knows that ultimately, the laws of economics reassert their grip on market activity. Investors back in 2000 would have done well to remember Horace’s ‘Ars Poetica’, in which he states: ‘Many shall be restored that are now fallen, and many shall fall that are now in honour.’

“For fall they did, and they fell hard. A near-sighted investor entering the market at its peak in March 2000 would face true devastation. A $10,000 investment in the 50 stocks with the highest price / sales ratios from the All Stocks universe would have been worth a mere $526 at the end of March 2003; worth just $1,081 if invested in the highest price / book stocks; $1,293 invested in the highest price / cashflow stocks, and $2,549 if invested in the 50 stocks with the highest p/e ratios. The devastation was so severe that even a $10,000 portfolio invested in 1997 and comprised of the highest price-to-book, price-to-cashflow, price-to-sales, and p/e stocks – while growing to $30,000 at the bubble’s peak – would have been worth just $4,500 by March 2003.”

In one respect, all we’re really seeing here over the long run is the miracle of compounding. Albert Einstein, it is said, once observed that the miracle of compound interest was the 8th wonder of the world. And the huge advantage that ‘value’ stocks have over ‘growth’ stocks, typically, is that they pay superior dividends.

The difference between value – what we might call ‘quality’ value, as opposed to stocks that might form value traps – is that it also offers a margin of safety (another Benjamin Graham coinage). Provided you’ve done your research properly, a true ‘quality value’ stock gets even more attractive as and when its share price falls. But a typical ‘growth’ stock – especially one bought at a significant premium to its fair value – doesn’t necessarily get any more attractive as its share price gets weaker. If it’s been bid up to some ridiculous overvaluation by excited growth investors, its share price decline can be massive and can last for years. Bear in mind the performance of Nasdaq after Jim Cramer’s contrarian recommendation of internet stocks cited above.

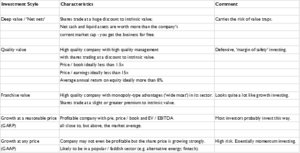

So value clearly means different things to different people. Our ‘take’ on the various sub-types of value and growth investing is shown in the table below:

One facet of value investing that reinforces the requirement for patience is the nature of the catalyst that will come to trigger all of that ‘hidden’ value to be recognised by the market.

Benjamin Graham was himself asked this question at a congressional hearing, before the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, in 1955:

The Chairman: “One other question.. When you find a special situation and you decide, just for illustration, that you can buy for $10 and it is worth $30, and you take a position, and then you cannot realize it until a lot of other people decide it is worth $30, how is that process brought about – by advertising, or what happens ?”

Benjamin Graham: “That is one of the mysteries of our business, and it is a mystery to me as well as to everybody else. We know from experience that eventually the market catches up with value. It realizes it in one way or another.”

In this respect, it might fairly be said that all genuine value investors come early to the party. They seek to acquire stakes in undervalued businesses before the market wakes up to their real worth. Sometimes well before. The nature of the catalyst to unlock that “hidden” value is never entirely clear. We just know that if a good value manager has done his homework, as opposed to falling in love with a value trap, that genuine value will be rewarded, in time. As Jeff Goldblum’s Dr. Malcolm says in ‘Jurassic Park’: nature finds a way.

But because that way is not always immediate, or obvious, the financial columnist Jonathan Davis is exactly right when he observes that

“Periods of excruciating short term underperformance are a burden that all genuine value investors have to endure.”

Or as the value manager Richard Oldfield puts it, in a phrase which became the title of his autobiography, successful value investing is ‘Simple but not easy’.

Enter Donald Trump

We know that the second iteration of Donald Trump as presidential candidate talked tough about immigration, trade and jobs. But now that Trump 2.0 has entered office, the rhetoric hasn’t softened any. Here is what the new president said as part of his (first) inauguration speech:

“Every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs will be made to benefit American workers and American families.”

The next word in that earlier speech was ‘Protection’. But to all intents and purposes it might as well have been ‘Protectionism’. And then, of course, we had the apparent chaos of February 2025’s proposed tariffs.

Economists don’t necessarily agree on all that much. But the profession is pretty much unanimous in its view that hiking tariffs during the early 1930s made the Great Depression that much worse.

In June 1930 Thomas Lamont, a partner at JP Morgan, was in despair at the outlook for trade:

“I almost went down on my knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot Tariff. That Act intensified nationalism all over the world.”

Lamont wasn’t alone. Irving Fisher, one of the most celebrated economists of the era, sponsored and circulated a petition against Smoot-Hawley signed by 1,028 fellow economists.

These efforts came to naught. As Smoot-Hawley was enacted on 17th June 1930, a total of 890 tariffs were increased.

The impact on trade, not least for the United States, was chilling. Unsurprisingly, America’s trade competitors retaliated. In the three years following the Great Crash of 1929, US GDP contracted, each year, by 10%. During the Great Depression, US imports and exports would fall by more than half.

One thing that leaps out from Benjamin Graham’s ‘The Intelligent Investor’ is that investors can expose themselves to significant risks by overpaying – even for high quality businesses. Quality, like value, is subjective – but both characteristics are impacted by extremes in price.

And they are also impacted by technocratic overreach. Government intervention, in short, doesn’t work. And if it does appear to work, it invariably works in a way counter to the one originally intended. There’s a quote attributed to the economist Milton Friedman:

“If you put the federal government in charge of the Sahara Desert, in five years there’d be a shortage of sand.”

The painful and self-destructive history of government intervention is well told in Robert Schuettinger and Eamonn Butler’s excellent history ‘Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls’. The clue is in the title. You can download a free PDF copy of this brilliant book here.

David Meiselman, in his foreword to ‘Forty Centuries’, raises an intriguing question:

“What, then, have price controls achieved in the recurrent struggle to restrain inflation and overcome shortages? The historical record is a grimly uniform sequence of repeated failure. Indeed, there is not a single episode where price controls have worked to stop inflation or cure shortages. Instead of curbing inflation, price controls add other complications to the inflation disease, such as black markets and shortages that reflect the waste and misallocation of resources caused by the price controls themselves. Instead of eliminating shortages, price controls cause or worsen shortages. By giving producers and consumers the wrong signals because “low” prices to producers limit supply and “low” prices to consumers stimulate demand, price controls widen the gap between supply and demand.

“Despite the clear lessons of history, many governments and public officials still hold the erroneous belief that price controls can and do control inflation. They thereby pursue monetary and fiscal policies that cause inflation, convinced that the inevitable cannot happen. When the inevitable does happen, public policy fails and hopes are dashed. Blunders mount, and faith in governments and government officials whose policies caused the mess declines. Political and economic freedoms are impaired and general civility suffers.”

So shelter from the approaching storms in defensive value – because the assaults on political and economic freedom have only just started – and general civility is likely going to suffer a whole lot more.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and also in systematic trend-following funds.

“All intelligent investing is value investing, acquiring more than you are paying for.”

Get your Free

financial review

The danger signs had been visible for quite some time, for those with the eyes to see. As early as October 1967, Warren Buffett was writing to his partners at the Buffett Partnership Ltd., warning that:

“The market environment has changed progressively.. resulting in a sharp diminution in the number of obvious quantitatively based investment bargains available..

“In my opinion what is resulting is speculation on an increasing scale.. we will not follow the frequently prevalent approach of investing in securities where an attempt to anticipate market action overrides business valuations. Such so-called ‘fashion’ investing has frequently produced very substantial and quick profits in recent years.. It does not completely satisfy my intellect (or perhaps my prejudices), and most definitely does not fit my temperament. I will not invest my own money based upon such an approach – hence, I will most certainly not do so with your money.”

By November 1967, Buffett was going to some lengths to manage his partners’ expectations. He pointed out that the partnership had $20 million invested in “controlled companies” (i.e. unlisted subsidiaries) and a further $16 million in short-term government debt – a total of $36 million in partners’ capital that would not benefit in any way from a stock market rally. This was not a judgment call on the level of the market, however, merely a reflection of the fact that “I can’t find any obviously profitable and safe places to put the money”.

By May 1969, Buffett had had enough. He wrote to advise his partners that he was winding up the partnership for good:

“I just don’t see anything available that gives any reasonable hope of delivering.. a good year and I have no desire to grope around, hoping to “get lucky” with other people’s money. I am not attuned to this market environment, and I don’t want to spoil a decent record by trying to play a game I don’t understand just so I can go out a hero.”

While Buffett was in the process of quietly exiting the stock market, other investors were piling into the shares of businesses that would become notorious as the ‘Nifty Fifty’ – those ‘glamour’ stocks, like IBM, Gillette, Coca-Cola and Xerox, that seemed to offer such stability (virtually none of them had cut their dividends since World War 2) combined with such superior prospects for growth (including international expansion) that they could justify practically any valuation afforded them by the marketplace, and defy any apparent weakness in the global economy.

The ‘Nifty Fifty’ came to be known as ‘one decision’ stocks: the only decision investors had to make was just how many of them to buy.

By 1972, the S&P 500 index was trading at a punchy 19 times earnings. The ‘Nifty Fifty’, on the other hand, stood at a p/e of 42. That was the average. Some of the individual nifties traded at eye-watering levels, factoring in a ridiculous level of optimism for the future. Avon Products traded at 65 times earnings. Walt Disney stood at 82 times. McDonald’s was at 86 times earnings. Polaroid sported a p/e of 91.

And then the market collapsed.

In the words of a Forbes columnist, the Nifty Fifty “were taken out and shot, one by one.”

From its high, Xerox stock fell by 71%. Avon Products fell by 86%. Polaroid’s decline was the most sickening: 91%.

Forbes issued a post mortem for these former wonder stocks:

“What held the Nifty Fifty up ? The same thing that held up tulip-bulb prices in long-ago Holland – popular delusions and the madness of crowds. The delusion was that these companies were so good it didn’t matter what you paid for them; their inexorable growth would bail you out.

“Obviously the problem was not with the companies but with the temporary insanity of institutional money managers – proving again that stupidity well-packaged can sound like wisdom. It was so easy to forget that no sizable company could possibly be worth over 50 times normal earnings.”

The bizarre thing about the investment markets is that if you simply hang around long enough, you get to see insanity repeat itself. Human nature never really changes. It took roughly a generation for the cult of the Nifty Fifty to repeat itself with the first wave of dot-bombs in 1999. Since we now operate in internet time, the delays between these peak waves of insanity are getting shorter and shorter. The Nifty Fifty has put in some recent reappearances, in the form of numerous cryptocurrencies, and a second (or is it third ?) Nasdaq mega-cap boom.

Like the Nifty Fifty, support for, and investor interest in, the wildly popular global tech mega-cap brand, for example, had a superficial grounding in reality. Financial repression had driven interest rates down to zero and in some cases below it. That essentially destroyed (and we think continues to invalidate) both cash and bonds as relevant asset classes for most investors – especially individuals – and effectively forced them into the welcoming embrace of the equity markets, in search of a positive real return. But which stocks to own ? Those investors who have stampeded into global mega-cap brands have done so for sane enough reasons. They think these stocks are safe. The businesses may well be, but safety in matters of investment is a function of price and valuation, not business quality. It is, in other words, all about value.

Many investors claim to be value investors, but what do they really mean by the term ?

Value is somewhat subjective, and to some extent it’s in the eye of the beholder. Your definition of value and ours are likely to be somewhat different. Human nature is like that. We have different preferences, different risk tolerances, different objectives.

But we all want a good deal.

Along the continuum of investing strategies, ‘deep value’ sits at one end: it is what Warren Buffett once described as ‘cigar butt’ investing – a cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it. It may not offer much of a smoke, “but the bargain purchase will make that puff all profit”.

Benjamin Graham, the spiritual father of value investing, recommended a particular type of ‘deep value’ opportunity in the form of so-called ‘net net’ stocks. A ‘net net’ stock is one where a company’s net cash and liquid assets add up to more than the entire market capitalisation of the company. In effect, you’re getting the business for free.

Two separate studies of ‘net nets’ point to the returns available from value investing.

The first, conducted by Professor Henry Oppenheimer across the US stock market between 1970 and 1983 (‘Ben Graham’s net current asset values: a performance update’) showed some impressive results. Whereas the market itself returned 11.5% per annum over the period in question, net net stocks returned 29.4% per annum. Almost three times as much.

The second, conducted by the behavioural economist James Montier, across global markets between 1985 and 2007, saw the markets themselves deliver an annual return of 17%. Net net stocks, however, returned 35% – almost twice as much. Perhaps there could be something behind deep value investing ?

One of the best exponents of deep value investing we know is the US manager Dave Iben of Kopernik Global Investors. When we first heard Iben speak at a meeting in London we were struck by a consistent refrain of what he looks for in an investment:

“I want half off.”

Whatever he’s considering buying, he wants to buy at a discount. The minimum discount he’s willing to accept is 50%. And if whatever he’s buying is in a risky market where the quality of corporate governance may be somewhat questionable, or where political risk might be more than usually acute, he wants even more off – perhaps as much as 80% or 90% versus ‘fair value’. So although the quality of these investments may be a little questionable, the deep discount at which they are sometimes available amounts to a margin of safety, of sorts.

And the biggest risk associated with ‘deep value’ relates to quality. A ‘deep value’ business may well be cheap, but it may also be cheap for a reason. A ‘deep value’ business runs the risk of turning into a ‘value trap’ – its shares never end up recovering toward a share price consistent with an investor’s assessment of its fair value. Capital invested in a ‘value trap’ never manages to escape from a fundamentally poorly performing company. Value traps are the stock market’s equivalent of black holes.

‘Growth’ sits at the other end of the scale. A ‘growth’ stock is widely perceived to be a better investment because the company’s revenues (if not its profits) are growing strongly. It is typically in a sexy ‘growth’ sector, like biotechnology, alternative energy, or fintech. Growth investors are essentially momentum investors – for as long as the stock price is rising, growth investors are more than happy to chug along with it. The biggest risk associated with ‘growth’ stocks is that that growth suddenly goes into reverse. Company revenues stop growing as quickly as they have in the past, or – heaven forbid – they go into reverse. Internet stocks were the classic example of growth stocks during the mid- to late-90s. Companies without profits and in many cases without even revenues could justify pretty much any valuation, on the grounds that they were growing so quickly they could ‘grow into’ those elevated valuations over time. It was important for growth investors simply to stake their claim and exploit ‘first mover advantage’. That was the theory, anyway.

One of the more notorious examples of a growth stock advocate was Jim Cramer of financial website TheStreet.com in February 2000. Delivering the keynote speech at the 6th Annual Internet and Electronic Conference and Exposition in New York, Cramer named 10 technology and internet companies and then issued the following recommendation:

“We are buying some of every one of these this morning as I give this speech. We buy them every day, particularly if they are down, which, no surprise given what they do, is very rare. And we will keep doing so until this period is over – and it is very far from ending. Heck, people are just learning these stories on Wall Street, and the more they come to learn, the more they love and own! Most of these companies don’t even have earnings per share, so we won’t have to be constrained by that methodology for quarters to come.”

Famous last words.

It turns out that Cramer inadvertently nailed the top of the first Internet boom. His speech was delivered within a month of Nasdaq’s March 2000 high. Nasdaq went on to fall by 80% over the next two years. Growth investing comes at a price. Or as Warren Buffett put it, it is difficult to buy what is popular and do well.

Why Buffett isn’t a value investor

Between deep value on one hand and growth on the other lie a selection of value strategies. A few summers ago we attended the London Value Investor Conference at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, near Parliament. 500 value managers from around the world were packed into the auditorium. The first speaker asked the floor a question: what type of investor are you ? Are you a classic ‘value’ manager ? We put our hand up, but we didn’t have much company. He then asked, are you a ‘franchise’ manager ? Almost everybody stuck their hand up. Value is clearly in the eye of the beholder.

Warren Buffett began his investment career as a value manager in the style of Benjamin Graham. Benjamin Graham’s ‘The Intelligent Investor’, first published in 1949, remains the Bible of value investing. Graham went out of his way to define investment as opposed to speculation, as follows:

“An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

To Graham, an investment and a ‘value’ investment were essentially the same thing. Value simply offered a greater margin of safety to the investor.

But something happened to Warren Buffett along the way. His holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, became too big for him to concentrate on value investing.

Genuine value investing has its limits.

Genuine value investing, especially in small and mid-cap companies, has size constraints.

Warren Buffett faced these constraints. At the time of his recent retirement from it, Berkshire Hathaway was a $1 trillion company by market cap. During his more recent years at the company, Buffett could not realistically buy small or mid-cap stocks (if he desired any meaningful impact on his overall portfolio). Berkshire Hathaway was and is simply too big.

So as Berkshire grew, Buffett was forced to shift his emphasis from Benjamin Graham-style value to what we might call ‘franchise’ value instead: businesses that enjoy a superior reputation with relation to their brands beyond those businesses’ plain balance sheet value. Which is another way of saying ‘growth’ stocks, since their shares are typically trading at a significant premium to their fair value. Buffett is fond of buying businesses with a “moat”: some seemingly unassailable position in the marketplace deriving from a monopoly-type market advantage. But shares in those type of businesses don’t come cheap, because almost everyone wants to own them. As he’s admitted, because of the scale of Berkshire’s business interests, Buffett / Berkshire now has to look for the market equivalent of elephants in order to move the dial on his investment portfolio. And as the fund manager Jim Slater was fond of saying, elephants don’t gallop. Berkshire, in other words, has to compromise when it comes to paying, and potentially overpaying, to own quality businesses (in some instances, outright).

So when (almost) everyone at the London Value Conference confessed to being a ‘franchise’ manager, what they really meant was they had stopped being a ‘value’ manager – either because it’s too difficult, or because there are too few opportunities, or both.

The late Canadian value manager Peter Cundill nicely expressed this problem in his autobiography ‘There’s always something to do’. Specifically, he advised readers that

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

Your edge over the professionals

But this is an area in which, as an individual investor, you have an advantage over ourselves. You don’t have to disclose your investments to anyone. You don’t have to worry about inflows and especially outflows from your fund. You don’t have to report your performance on a daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly basis to anybody. As managers of a UK regulated fund we have to do all of the above. We’re comfortable with the swings and arrows of the market’s outrageous fortune – but our investors may not be, so we’re continually at the mercy of those inflows and outflows. As Peter Cundill correctly pointed out, most investors do not possess an overabundance of patience.

Which is a shame. Because value investing is the best performing investment strategy there is. In his fabulous study of market returns, ‘What works on Wall Street’ (we use the 2005 edition published by McGraw-Hill), James O’Shaughnessy points to the long term outperformance of value metrics versus growth.

Take the following chart. It shows the compound annual average rates of return for various strategies drawn from the broader US market over a period of over 50 years.

Value of $10,000 invested in various strategies for the 52 years ending in December 2003

Source: ‘What Works on Wall Street’ by James P. O’Shaughnessy

The figures are illuminating, and the data set sufficiently large, in our opinion, to address any questions about selectivity or survivorship bias.

All of those metrics associated with ‘growth’ investing strategies (buying stocks on a high price to sales ratio (PSR), buying stocks on high price / cashflow, buying stocks on a high price / book ratio, buying stocks on a high p/e ratio) delivered significantly worse returns than those metrics associated with classic Ben Graham ‘value’ investing.

If you bought high yielding stocks – irrespective of the quality of the businesses – you made, on average 13.35%.

If you bought stocks on a high price / sales ratio, you did appallingly, averaging just 1.25% per annum.

But if you did the exact opposite, and selected stocks trading on a low price / sales ratio, you made out like a bandit, with average annual returns of 15.95%.

Price / cashflow saw the same effect. A ‘growth’ bias made you 5.16%, on average. A ‘value’ bias earned you 15.47%.

Price / book saw the same effect. A ‘growth’ bias gave you 6.52%, on average. A ‘value’ bias saw you earn 15.95%.

Price / earnings saw the same effect. ‘Growth’ investors favouring high p/e stocks earned 8.78%, on average. ‘Value’ investors favouring low p/e stocks earned 13.77%.

This analysis is staggering. The gulf between the long term returns from ‘growth’ and ‘value’ strategies is eye-opening. And note, again, that this study takes no account of the more subjective, qualitative aspects of investing such as the quality of the business or the calibre of management – this is just raw data we’re looking at.

But the message is clear. While ‘growth’ stocks can clearly outperform over the shorter term, ‘value’ wins out for the patient investor. Take the (first) Nasdaq boom of the late 1990s. ‘Growth’ stocks delivered stellar returns for a few years – and then gave them all back, with interest. ‘Value’ underperformed for a period, but any patient ‘value’ investor was vindicated from March 2000 onwards.

As O’Shaughnessy puts it,

“..anyone familiar with past market bubbles knows that ultimately, the laws of economics reassert their grip on market activity. Investors back in 2000 would have done well to remember Horace’s ‘Ars Poetica’, in which he states: ‘Many shall be restored that are now fallen, and many shall fall that are now in honour.’

“For fall they did, and they fell hard. A near-sighted investor entering the market at its peak in March 2000 would face true devastation. A $10,000 investment in the 50 stocks with the highest price / sales ratios from the All Stocks universe would have been worth a mere $526 at the end of March 2003; worth just $1,081 if invested in the highest price / book stocks; $1,293 invested in the highest price / cashflow stocks, and $2,549 if invested in the 50 stocks with the highest p/e ratios. The devastation was so severe that even a $10,000 portfolio invested in 1997 and comprised of the highest price-to-book, price-to-cashflow, price-to-sales, and p/e stocks – while growing to $30,000 at the bubble’s peak – would have been worth just $4,500 by March 2003.”

In one respect, all we’re really seeing here over the long run is the miracle of compounding. Albert Einstein, it is said, once observed that the miracle of compound interest was the 8th wonder of the world. And the huge advantage that ‘value’ stocks have over ‘growth’ stocks, typically, is that they pay superior dividends.

The difference between value – what we might call ‘quality’ value, as opposed to stocks that might form value traps – is that it also offers a margin of safety (another Benjamin Graham coinage). Provided you’ve done your research properly, a true ‘quality value’ stock gets even more attractive as and when its share price falls. But a typical ‘growth’ stock – especially one bought at a significant premium to its fair value – doesn’t necessarily get any more attractive as its share price gets weaker. If it’s been bid up to some ridiculous overvaluation by excited growth investors, its share price decline can be massive and can last for years. Bear in mind the performance of Nasdaq after Jim Cramer’s contrarian recommendation of internet stocks cited above.

So value clearly means different things to different people. Our ‘take’ on the various sub-types of value and growth investing is shown in the table below:

One facet of value investing that reinforces the requirement for patience is the nature of the catalyst that will come to trigger all of that ‘hidden’ value to be recognised by the market.

Benjamin Graham was himself asked this question at a congressional hearing, before the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, in 1955:

The Chairman: “One other question.. When you find a special situation and you decide, just for illustration, that you can buy for $10 and it is worth $30, and you take a position, and then you cannot realize it until a lot of other people decide it is worth $30, how is that process brought about – by advertising, or what happens ?”

Benjamin Graham: “That is one of the mysteries of our business, and it is a mystery to me as well as to everybody else. We know from experience that eventually the market catches up with value. It realizes it in one way or another.”

In this respect, it might fairly be said that all genuine value investors come early to the party. They seek to acquire stakes in undervalued businesses before the market wakes up to their real worth. Sometimes well before. The nature of the catalyst to unlock that “hidden” value is never entirely clear. We just know that if a good value manager has done his homework, as opposed to falling in love with a value trap, that genuine value will be rewarded, in time. As Jeff Goldblum’s Dr. Malcolm says in ‘Jurassic Park’: nature finds a way.

But because that way is not always immediate, or obvious, the financial columnist Jonathan Davis is exactly right when he observes that

“Periods of excruciating short term underperformance are a burden that all genuine value investors have to endure.”

Or as the value manager Richard Oldfield puts it, in a phrase which became the title of his autobiography, successful value investing is ‘Simple but not easy’.

Enter Donald Trump

We know that the second iteration of Donald Trump as presidential candidate talked tough about immigration, trade and jobs. But now that Trump 2.0 has entered office, the rhetoric hasn’t softened any. Here is what the new president said as part of his (first) inauguration speech:

“Every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs will be made to benefit American workers and American families.”

The next word in that earlier speech was ‘Protection’. But to all intents and purposes it might as well have been ‘Protectionism’. And then, of course, we had the apparent chaos of February 2025’s proposed tariffs.

Economists don’t necessarily agree on all that much. But the profession is pretty much unanimous in its view that hiking tariffs during the early 1930s made the Great Depression that much worse.

In June 1930 Thomas Lamont, a partner at JP Morgan, was in despair at the outlook for trade:

“I almost went down on my knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot Tariff. That Act intensified nationalism all over the world.”

Lamont wasn’t alone. Irving Fisher, one of the most celebrated economists of the era, sponsored and circulated a petition against Smoot-Hawley signed by 1,028 fellow economists.

These efforts came to naught. As Smoot-Hawley was enacted on 17th June 1930, a total of 890 tariffs were increased.

The impact on trade, not least for the United States, was chilling. Unsurprisingly, America’s trade competitors retaliated. In the three years following the Great Crash of 1929, US GDP contracted, each year, by 10%. During the Great Depression, US imports and exports would fall by more than half.

One thing that leaps out from Benjamin Graham’s ‘The Intelligent Investor’ is that investors can expose themselves to significant risks by overpaying – even for high quality businesses. Quality, like value, is subjective – but both characteristics are impacted by extremes in price.

And they are also impacted by technocratic overreach. Government intervention, in short, doesn’t work. And if it does appear to work, it invariably works in a way counter to the one originally intended. There’s a quote attributed to the economist Milton Friedman:

“If you put the federal government in charge of the Sahara Desert, in five years there’d be a shortage of sand.”

The painful and self-destructive history of government intervention is well told in Robert Schuettinger and Eamonn Butler’s excellent history ‘Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls’. The clue is in the title. You can download a free PDF copy of this brilliant book here.

David Meiselman, in his foreword to ‘Forty Centuries’, raises an intriguing question:

“What, then, have price controls achieved in the recurrent struggle to restrain inflation and overcome shortages? The historical record is a grimly uniform sequence of repeated failure. Indeed, there is not a single episode where price controls have worked to stop inflation or cure shortages. Instead of curbing inflation, price controls add other complications to the inflation disease, such as black markets and shortages that reflect the waste and misallocation of resources caused by the price controls themselves. Instead of eliminating shortages, price controls cause or worsen shortages. By giving producers and consumers the wrong signals because “low” prices to producers limit supply and “low” prices to consumers stimulate demand, price controls widen the gap between supply and demand.

“Despite the clear lessons of history, many governments and public officials still hold the erroneous belief that price controls can and do control inflation. They thereby pursue monetary and fiscal policies that cause inflation, convinced that the inevitable cannot happen. When the inevitable does happen, public policy fails and hopes are dashed. Blunders mount, and faith in governments and government officials whose policies caused the mess declines. Political and economic freedoms are impaired and general civility suffers.”

So shelter from the approaching storms in defensive value – because the assaults on political and economic freedom have only just started – and general civility is likely going to suffer a whole lot more.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and also in systematic trend-following funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price