“Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet.”

Get your Free

financial review

There is a story – perhaps apocryphal – that the US brokerage firm Fidelity once conducted a survey of its clients to assess its investment performance. After the survey it turned out that its most successful clients were dead. Its second most successful clients had forgotten that they even had a Fidelity brokerage account.

If this isn’t true, it ought to be.

Investment adviser Rob Kirby tells a similar story, of what he calls the “Coffee Can portfolio”. He once had husband and wife clients who religiously followed the recommendations of his brokerage firm. More specifically, the wife followed the recommendations, and dutifully bought and sold stocks according to the firm’s research guidance. The husband, on the other hand, simply put $5,000 into each of the firm’s “Buy” recommendations and then locked the share certificates into a safety deposit box.

On the death of her husband, his widow decided to amalgamate their two stock portfolios. The value of the husband’s portfolio dwarfed hers. Although several holdings had sunk to $2,000, they were comfortably offset by the number of holdings that had risen above $100,000. One holding alone – in Xerox – was worth more than $800,000.

Lesson: once you have finished constructing a diversified portfolio, leave it well alone.

But this is easier said than done. Blaise Pascal once said that all men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone. The Canadian value investor Peter Cundill expressed a similar sentiment:

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

The notorious stock speculator Jesse Livermore once remarked that

“After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: it never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It was always my sitting. Got that ? My sitting tight !”

The problem we all face is that Pascal’s quiet room is an ideal. The real world is too noisy. This is the reason we recommend going on a “news diet”. (You can read more about the “news diet” here.)

Part of the problem is that the brokerage industry doesn’t want you to sit in Pascal’s quiet room. Stockbrokers make money from trading commissions. Your impatience leads to their wealth.

In 1997, Terrance Odean, a behavioural economist at the University of California, asked in a paper, “Why do investors trade too much?”

Over a seven-year period between 1987 and 1993, Odean tracked almost 100,000 trades made by 10,000 randomly selected clients of a major discount broker. It turns out that investors sold and subsequently bought back almost 80% of their portfolios each year.

He went on to compare the client portfolios with the broad market over three periods: four months, 12 months and two years.

In each case, the stocks that investors bought consistently lagged the market. The stocks that they sold consistently went on to beat the market.

In a follow-up paper three years later (“Trading is hazardous to your wealth”), Odean monitored the performance of 6,465 households. On average, those who traded most frequently had the worst returns, while those who traded the least enjoyed the highest returns.

Nor is this a problem limited to the world of stocks. ‘Investors’ in funds are just as guilty. Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard Group once pointed out that the performance gap between fund and fund investor since the mid-1990s averaged out at 2.2% per annum. The average fund will lag the market after fees, but the average investor will lag even more, to the order of over 2% each year, through overtrading units in the fund.

The data for ETFs (exchange-traded funds, typically low-cost funds that are listed on stock exchanges and that can be traded just like stocks) is even worse. Bogle pointed out that the average annual turnover rate of investors who owned ETFs was a monstrous 1,400% – or 140 times the annual redemption rate of traditional index funds.

Our three favourite words in investing are “margin of safety”. Our second three favourite words in investing are “buy and forget”.

So much for the perils of overtrading. You can improve your portfolio returns significantly simply by leaving well alone. How else can you improve your portfolio performance ?

Not all equities are created equal. Before we even get to the level of specific stocks, it helps to know that certain styles simply have a better chance of outperforming the market, and of course other investors, over the longer term.

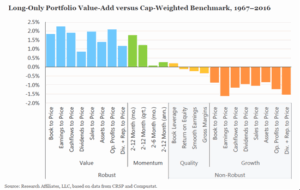

John West, Vitali Kalesnik and Mark Clements of the US investment firm Research Affiliates crunched the numbers for the entire stockmarket for 50 years. What they found was more than a little intriguing, and their results are shown below.

They split the market into four categories: “value” (decent companies whose shares are trading at inexpensive prices); “momentum” (companies whose share prices are rising strongly); “quality” (decent companies viewed as bulletproof when it comes to reliability of earnings); and “growth” (companies whose shares are expensive relative to their underlying earnings).

It turns out that “value” stocks typically outperformed the market, on average, by anything from 0.5% to over 2% per annum, depending on precisely which value metric you favoured.

“Momentum” stocks also outperformed.

This chimes with our own suspicions about the stock market: that there are only two sustainable and enduring ways of making money from stocks, namely value and momentum, in that order.

Research Affiliates then found that two popular styles, “quality” and “growth”, actually destroyed value over the longer term – the chart above shows just how badly.

Clearly “quality” and “growth” enjoy their time in the sun – and they have done, quite remarkably, for much of the last decade or so, in the form of US Big Tech and the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’. Perhaps it really is different this time, and we inhabit a new investment paradigm. We happen to suspect otherwise, given that human nature is largely immutable through the ages. We shall see. But when markets fall, “quality” and “growth” tend to fall harder than the rest, not least because, by overpaying for them, their shareholders don’t benefit from the “margin of safety” that is part and parcel of value investing.

There is also growing anecdotal evidence of “quality” and “growth” stocks starting to lose their shine.

As the great value investor Benjamin Graham pointed out (emphasis ours),

“Investors do not make mistakes, or bad mistakes, in buying good stocks at fair prices. They make their serious mistakes by buying poor stocks, particularly the ones that are pushed for various reasons. And sometimes – in fact very frequently – they make mistakes by buying good stocks in the upper reaches of bull markets.”

This is surely a fair description of the current financial environment – “the upper reaches of bull markets”.

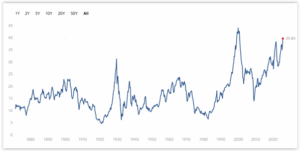

Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio for the S&P 500 stock index, which takes the ten-year smoothed average of corporate earnings to iron out short-term volatility, now stands at c. 40 times – just before the 1929 Crash it stood, briefly, at just over 30 times. Its long-run average is around 17 times. Assuming that markets revert to the mean, which seems a reasonable supposition to us, the US stock market is trading at well over twice its historic fair value.

Shiller cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio for the S&P 500 stock index, 1870 to 2025

Source: https://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe.

The response to the problem of overvaluation is not to liquidate your portfolio and hide in a bunker. The rational response to a multi-year bull market in growth stocks is to diversify among sensible asset classes and then concentrate on value investments.

Value investing is the antidote to overvaluation because it doesn’t participate in it to begin with.

Unfortunately, the cult of indexation has been given a recent boost by the recent Gadarene inflows into low cost ETFs. It makes sense to get low cost exposure to “the markets” when the markets themselves are cheap. When they’re trading at their highest levels in history, it makes much more sense to be discerning, and to favour value (just as Research Affiliates implicitly recommend). Sadly, the high priests of finance are not on your side here.

Edwin Levy and Michael Harkins of the US investment advisers Levy, point out the aesthetic poverty of the Emperor’s new clothes in devastating manner. They question the efficient market hypothesis advocated by Professor Burton Malkiel in his book A Random Walk Down Wall Street as follows (their original letter was published in January 2005 but is, essentially, timeless):

“In his speech of May 1984, famous throughout the value investing world, and utterly obscure without it, Buffett pointed out that Benjamin Graham, the founder of the value style of investing and Buffett’s original finance professor at Columbia, only hired four people to work for his investment firm, Graham-Newman, in its entire history. After Graham-Newman was wound up in 1957, three of those hires went on to manage their own firms; Walter Schloss, Tom Knapp, and Warren Buffett. All three subsequently enjoyed phenomenal investment success by the time of Buffett’s talk in 1984. Let us stop here and ask, what are the odds that three guys at an obscure shop should just get lucky beyond the bounds of any lottery ever known? Then in 1969, Buffett decided to close up shop, and he handed his investors over to Bill Ruane at the Sequoia Fund. Guess what? Ruane was lucky too. So that by 1984, each of these four managers had records of at least 25 years length that were far better than chance would allow. But this is 2004, so what is our point in bringing up some mouldy magazine with an obscure story ?

“Just this. Buffett identified in 1984 nine investment records in all that were stellar, and were all directly related to value investing, the idea that you should only buy stocks for the long term that sell at significant discounts to the worth a knowledgeable buyer would pay for the whole business. You should throw in a sizeable margin of safety, meaning make it a really big discount. Then throw out every other idea, meaning turn off CNBC, and leave it off. So, how has this lucky group done since they were identified as lucky twenty years ago ?

“Tom Knapp went on to manage Tweedy, Browne, which today runs three major pools of capital; a global mutual fund, an American mutual fund, and the original partnership Buffett quoted. There has been no reverting to the mean for Tweedy, Browne. All three branches of the firm have outperformed every reasonable bench mark known. Bill Ruane’s Sequoia Fund is still around, and while it hasn’t taken in new investors since 1982, as of the third quarter of 2004 it has handily outperformed the S&P Index 15.5% to 12.8%. Walter Schloss compounded money from 1983 to 2001 at a rate of 15.2%, when he closed up shop at age 86. You might note that Schloss was 68 at the time Buffett mentioned him in 1984, and he worked most of the next 18 years as a one man band without a successor, meaning not one consultant in the country would have hired him, and doesn’t that say something about consultants ?

“Then there are the separate records of Charles Munger and Warren Buffett, who combined to form Berkshire Hathaway. Their stock is $86,000 a share as we write and was about $1,400 a share when Buffett gave his lecture. You do the math. Two of the other fellows honourably mentioned grew so rich so rapidly they retired from running public money and no longer produce public records. Lastly, the Washington Post retirement plan has been so overfunded it regularly sends back checks from the plan to the corporation, which happens in corporate America about as frequently as snow in hell. These fellows all just got lucky again? You might consider this. Tom Knapp retired from Tweedy, Browne many years ago and Ruane, Cuniff has hired a fair number of younger investment managers. Yet these firms haven’t skipped a beat. So these lucky people know other lucky people on sight, and they hire them immediately? How do they do that? Indeed, in what way are these lucky luckies lucky? Are they all 6 feet 6 inches tall, with 25 inch waists and long flowing hair? Prodigious athletic skills perhaps? Er, no. No, no. They aren’t much to look at at all. They win no other of life’s lotteries, they are just lucky with money, or so the professoriate would have you believe.”

These are undoubtedly challenging times for investors. With bond yields grinding higher in a reflection of the broad insolvency of the West, and many equity markets having soared through the roof, safe havens are at something of a premium. But there is no need for despair. Simply diversify sensibly, avoid the more obvious ‘red flags’, and concentrate on value – and sensibly priced real assets. Then all you have to do is wait.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and real assets, and also in systematic trend-following funds.

“Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet.”

Get your Free

financial review

There is a story – perhaps apocryphal – that the US brokerage firm Fidelity once conducted a survey of its clients to assess its investment performance. After the survey it turned out that its most successful clients were dead. Its second most successful clients had forgotten that they even had a Fidelity brokerage account.

If this isn’t true, it ought to be.

Investment adviser Rob Kirby tells a similar story, of what he calls the “Coffee Can portfolio”. He once had husband and wife clients who religiously followed the recommendations of his brokerage firm. More specifically, the wife followed the recommendations, and dutifully bought and sold stocks according to the firm’s research guidance. The husband, on the other hand, simply put $5,000 into each of the firm’s “Buy” recommendations and then locked the share certificates into a safety deposit box.

On the death of her husband, his widow decided to amalgamate their two stock portfolios. The value of the husband’s portfolio dwarfed hers. Although several holdings had sunk to $2,000, they were comfortably offset by the number of holdings that had risen above $100,000. One holding alone – in Xerox – was worth more than $800,000.

Lesson: once you have finished constructing a diversified portfolio, leave it well alone.

But this is easier said than done. Blaise Pascal once said that all men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone. The Canadian value investor Peter Cundill expressed a similar sentiment:

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

The notorious stock speculator Jesse Livermore once remarked that

“After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: it never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It was always my sitting. Got that ? My sitting tight !”

The problem we all face is that Pascal’s quiet room is an ideal. The real world is too noisy. This is the reason we recommend going on a “news diet”. (You can read more about the “news diet” here.)

Part of the problem is that the brokerage industry doesn’t want you to sit in Pascal’s quiet room. Stockbrokers make money from trading commissions. Your impatience leads to their wealth.

In 1997, Terrance Odean, a behavioural economist at the University of California, asked in a paper, “Why do investors trade too much?”

Over a seven-year period between 1987 and 1993, Odean tracked almost 100,000 trades made by 10,000 randomly selected clients of a major discount broker. It turns out that investors sold and subsequently bought back almost 80% of their portfolios each year.

He went on to compare the client portfolios with the broad market over three periods: four months, 12 months and two years.

In each case, the stocks that investors bought consistently lagged the market. The stocks that they sold consistently went on to beat the market.

In a follow-up paper three years later (“Trading is hazardous to your wealth”), Odean monitored the performance of 6,465 households. On average, those who traded most frequently had the worst returns, while those who traded the least enjoyed the highest returns.

Nor is this a problem limited to the world of stocks. ‘Investors’ in funds are just as guilty. Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard Group once pointed out that the performance gap between fund and fund investor since the mid-1990s averaged out at 2.2% per annum. The average fund will lag the market after fees, but the average investor will lag even more, to the order of over 2% each year, through overtrading units in the fund.

The data for ETFs (exchange-traded funds, typically low-cost funds that are listed on stock exchanges and that can be traded just like stocks) is even worse. Bogle pointed out that the average annual turnover rate of investors who owned ETFs was a monstrous 1,400% – or 140 times the annual redemption rate of traditional index funds.

Our three favourite words in investing are “margin of safety”. Our second three favourite words in investing are “buy and forget”.

So much for the perils of overtrading. You can improve your portfolio returns significantly simply by leaving well alone. How else can you improve your portfolio performance ?

Not all equities are created equal. Before we even get to the level of specific stocks, it helps to know that certain styles simply have a better chance of outperforming the market, and of course other investors, over the longer term.

John West, Vitali Kalesnik and Mark Clements of the US investment firm Research Affiliates crunched the numbers for the entire stockmarket for 50 years. What they found was more than a little intriguing, and their results are shown below.

They split the market into four categories: “value” (decent companies whose shares are trading at inexpensive prices); “momentum” (companies whose share prices are rising strongly); “quality” (decent companies viewed as bulletproof when it comes to reliability of earnings); and “growth” (companies whose shares are expensive relative to their underlying earnings).

It turns out that “value” stocks typically outperformed the market, on average, by anything from 0.5% to over 2% per annum, depending on precisely which value metric you favoured.

“Momentum” stocks also outperformed.

This chimes with our own suspicions about the stock market: that there are only two sustainable and enduring ways of making money from stocks, namely value and momentum, in that order.

Research Affiliates then found that two popular styles, “quality” and “growth”, actually destroyed value over the longer term – the chart above shows just how badly.

Clearly “quality” and “growth” enjoy their time in the sun – and they have done, quite remarkably, for much of the last decade or so, in the form of US Big Tech and the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’. Perhaps it really is different this time, and we inhabit a new investment paradigm. We happen to suspect otherwise, given that human nature is largely immutable through the ages. We shall see. But when markets fall, “quality” and “growth” tend to fall harder than the rest, not least because, by overpaying for them, their shareholders don’t benefit from the “margin of safety” that is part and parcel of value investing.

There is also growing anecdotal evidence of “quality” and “growth” stocks starting to lose their shine.

As the great value investor Benjamin Graham pointed out (emphasis ours),

“Investors do not make mistakes, or bad mistakes, in buying good stocks at fair prices. They make their serious mistakes by buying poor stocks, particularly the ones that are pushed for various reasons. And sometimes – in fact very frequently – they make mistakes by buying good stocks in the upper reaches of bull markets.”

This is surely a fair description of the current financial environment – “the upper reaches of bull markets”.

Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio for the S&P 500 stock index, which takes the ten-year smoothed average of corporate earnings to iron out short-term volatility, now stands at c. 40 times – just before the 1929 Crash it stood, briefly, at just over 30 times. Its long-run average is around 17 times. Assuming that markets revert to the mean, which seems a reasonable supposition to us, the US stock market is trading at well over twice its historic fair value.

Shiller cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio for the S&P 500 stock index, 1870 to 2025

Source: https://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe.

The response to the problem of overvaluation is not to liquidate your portfolio and hide in a bunker. The rational response to a multi-year bull market in growth stocks is to diversify among sensible asset classes and then concentrate on value investments.

Value investing is the antidote to overvaluation because it doesn’t participate in it to begin with.

Unfortunately, the cult of indexation has been given a recent boost by the recent Gadarene inflows into low cost ETFs. It makes sense to get low cost exposure to “the markets” when the markets themselves are cheap. When they’re trading at their highest levels in history, it makes much more sense to be discerning, and to favour value (just as Research Affiliates implicitly recommend). Sadly, the high priests of finance are not on your side here.

Edwin Levy and Michael Harkins of the US investment advisers Levy, point out the aesthetic poverty of the Emperor’s new clothes in devastating manner. They question the efficient market hypothesis advocated by Professor Burton Malkiel in his book A Random Walk Down Wall Street as follows (their original letter was published in January 2005 but is, essentially, timeless):

“In his speech of May 1984, famous throughout the value investing world, and utterly obscure without it, Buffett pointed out that Benjamin Graham, the founder of the value style of investing and Buffett’s original finance professor at Columbia, only hired four people to work for his investment firm, Graham-Newman, in its entire history. After Graham-Newman was wound up in 1957, three of those hires went on to manage their own firms; Walter Schloss, Tom Knapp, and Warren Buffett. All three subsequently enjoyed phenomenal investment success by the time of Buffett’s talk in 1984. Let us stop here and ask, what are the odds that three guys at an obscure shop should just get lucky beyond the bounds of any lottery ever known? Then in 1969, Buffett decided to close up shop, and he handed his investors over to Bill Ruane at the Sequoia Fund. Guess what? Ruane was lucky too. So that by 1984, each of these four managers had records of at least 25 years length that were far better than chance would allow. But this is 2004, so what is our point in bringing up some mouldy magazine with an obscure story ?

“Just this. Buffett identified in 1984 nine investment records in all that were stellar, and were all directly related to value investing, the idea that you should only buy stocks for the long term that sell at significant discounts to the worth a knowledgeable buyer would pay for the whole business. You should throw in a sizeable margin of safety, meaning make it a really big discount. Then throw out every other idea, meaning turn off CNBC, and leave it off. So, how has this lucky group done since they were identified as lucky twenty years ago ?

“Tom Knapp went on to manage Tweedy, Browne, which today runs three major pools of capital; a global mutual fund, an American mutual fund, and the original partnership Buffett quoted. There has been no reverting to the mean for Tweedy, Browne. All three branches of the firm have outperformed every reasonable bench mark known. Bill Ruane’s Sequoia Fund is still around, and while it hasn’t taken in new investors since 1982, as of the third quarter of 2004 it has handily outperformed the S&P Index 15.5% to 12.8%. Walter Schloss compounded money from 1983 to 2001 at a rate of 15.2%, when he closed up shop at age 86. You might note that Schloss was 68 at the time Buffett mentioned him in 1984, and he worked most of the next 18 years as a one man band without a successor, meaning not one consultant in the country would have hired him, and doesn’t that say something about consultants ?

“Then there are the separate records of Charles Munger and Warren Buffett, who combined to form Berkshire Hathaway. Their stock is $86,000 a share as we write and was about $1,400 a share when Buffett gave his lecture. You do the math. Two of the other fellows honourably mentioned grew so rich so rapidly they retired from running public money and no longer produce public records. Lastly, the Washington Post retirement plan has been so overfunded it regularly sends back checks from the plan to the corporation, which happens in corporate America about as frequently as snow in hell. These fellows all just got lucky again? You might consider this. Tom Knapp retired from Tweedy, Browne many years ago and Ruane, Cuniff has hired a fair number of younger investment managers. Yet these firms haven’t skipped a beat. So these lucky people know other lucky people on sight, and they hire them immediately? How do they do that? Indeed, in what way are these lucky luckies lucky? Are they all 6 feet 6 inches tall, with 25 inch waists and long flowing hair? Prodigious athletic skills perhaps? Er, no. No, no. They aren’t much to look at at all. They win no other of life’s lotteries, they are just lucky with money, or so the professoriate would have you believe.”

These are undoubtedly challenging times for investors. With bond yields grinding higher in a reflection of the broad insolvency of the West, and many equity markets having soared through the roof, safe havens are at something of a premium. But there is no need for despair. Simply diversify sensibly, avoid the more obvious ‘red flags’, and concentrate on value – and sensibly priced real assets. Then all you have to do is wait.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and real assets, and also in systematic trend-following funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price